Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Mary Beard on politicizing Latin

Beard's recent post on Latin as a political straw man is a handy summary of arguments for and against the study of Classics.

(Lots of great stuff in the comments as well -- LOL at the arguments over whether Marx's thesis is boring or not.)

image credit Pin It

New t-shirt: "The Romans, kicking butt and taking names"

For the first time in a while, a new t-shirt in the Classics Daily shop: "Romani: clunes laedentes et nomina capientes ab urbe condita (753)" = "The Romans: kicking butt and taking names since the founding of the city (753)."

This design was inspired by a recent conversation with the spouse. We're eagerly awaiting season 2 of Game of Thrones (being poor folk who have to wait and watch it on DVD). I asked my husband what he thought our favorite character Tyrion Lannister might be up to, and he said, "oh, kicking a** and taking names."

Perhaps thinking of the many Roman emperors who overcame challenges in the service of butt-kicking (including the epileptic Julius Caesar), I thought the sentiment deserved a t-shirt.

UPDATED: now available as a mug. Pin It

Thursday, June 21, 2012

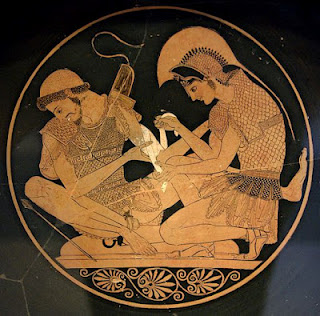

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

Madeline Miller's novel is an engaging and quite moving version of the life of Achilles and Patroclus, whom she presents as lovers.

I understand how some Amazon reviews have a problem with the way battle scenes are presented. But this is not a book about the reality of war. That is made clear fairly early, when the young Achilles does not practice fighting in front of anyone else.

"My mother has forbidden it. Because of the prophecy.""What prophecy?" …."That I will be the best warrior of my generation."It sounded like something a young child would claim, in make-believe. But he said it as simply as if he was giving his name. (p. 38)

Later, Patroclus describes Achilles' fighting as something from which Achilles himself is quite detached ("'They could not get close enough to touch me,' he said. There was a sort of wondering triumph in his voice." [p. 222]). The Trojan war has such a heavy admixture of the supernatural that realistic battle scenes would be out of place.

The heart of Miller's story is the time the boys spend with Chiron on Mount Pelion. Going to Pelion is the first substantial risk Patroclus takes for Achilles' sake. His mother Thetis believes Patroclus is too lowborn and too ordinary to be her son's companion, and has expressly forbidden that he accompany Achilles. After a trial period Chiron allows him to stay anyway. Warfare is (perhaps surprisingly) not a focus of Chiron's teaching. Rather, the boys learn music, healing, survival skills and ethics. When the couple is at Troy and living under the shadow of Achilles' imminent death Patroclus frequently recalls conversations they had or skills they learned on Pelion.

Chiron had once said that nations were the most foolish of mortal inventions. "No man is worth more than another, wherever he is from."

"But what if he is your friend?" Achilles had asked him, feet kicked up on the wall of the rose-quartz cave. "Or your brother? Should you treat him the same as a stranger?" (p. 298)

In conclusion, Miller's Patroclus may well be more sensitive and articulate than were most Bronze Age Greek men, and the experience of average people in war is given rather short shrift. But her observant and emotionally astute hero gives us a marvelously detailed portrait of Homeric society, the imagined prehistory of Greece.

image credit

Pin It

image credit

Monday, June 18, 2012

Greek Poetry and 'Treme'

The husband and I have been watching Treme on DVD, and I've been really drawn to the storyline that has to do with Mardi Gras Indians. The season 1 finale suggested to me some ways that this New Orleans custom resonates with ancient Greek celebrations.

Mardi Gras Indians are African-American clubs that dress and parade in elaborate feathered costumes, that must be made new every year. They compete with other tribes in musical skills and in the 'prettiness' of their costumes. The tribes include a 'spy', who goes ahead to watch for other tribes, a flag carrier, and a 'big chief'.

On the show, Albert, a Mardi Gras Indian chief, is determined to bring back the other members of his 'tribe', scattered by Hurricane Katrina, so they can march on Mardi Gras.

It's obviously a fascinating cultural custom, but I wondered why I felt so drawn to it. Then it occurred to me that Mardi Gras Indian represent both an oral tradition and a sense of occasion very similar to the Ancient Greeks'. Just as Pindar's victory odes were intended for a particular occasion, and are arguably diminished as texts only, so the tribes' costumes are for that particular night, and devalued after that. (Albert is shocked when his flag bearer wants to reuse a costume from last year, for example.)

The video is of a real-life Mardi Gras parade. If you don't have time to watch it all, you might skip to around 8:00, where two chiefs face off in a musical competition.

Pin It

Labels:

ancient Greek culture,

Mardi Gras Indians,

Pindar,

Treme HBO

Saturday, June 16, 2012

Antigonick by Anne Carson

Anne Carson's new translation of Sophocles' Antigone looks exciting. Attempting to modernize tragedy is nothing new ("How is a Greek chorus like a lawyer? / They're both in the business of searching for a precedent") but her simultaneous celebration of tragedy's convoluted language makes for an intriguing mix.

With the current emphasis on making classics 'relateable', it's nice to be reminded of that magical moment when you first learned Greek and were drawn to its weirdness (At least, that was the effect passages like this had on me):

"Many terribly quiet customers exist but none more / terribly quiet than man / his footsteps pass so perilously soft across the sea … and every Tuesday / down he grinds the unastonishable earth / with horse and shatter … Every outlet works but one / : Death stays dark."See the Guardian's review for more. I'm planning to pick up a copy as soon as I'm done with The Song of Achilles.

image credit

Pin It

Labels:

Anne Carson,

Antigone,

Antigonick,

Greek tragedy,

Sophocles

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

It's like being a professor, only more so

|

| Archaeological display in the Athens metro |

image credit Pin ItDespite its relatively low pay, the profession of archaeology has long been held in high esteem in Greece; it is a job that children aspire to, like becoming a doctor. And in a country where the public sector has been plagued for decades with corruption, archaeologists have retained a reputation as generally honorable and hard-working.“They used to say that we were a special race,” said Alexandra Christopoulou, the deputy director of the National Archaeological Museum. “We worked overtime without getting paid for it — a rarity in Greece — because we really loved what we did.”

Cool Greek word

ὁμοφροσύνη

homophrosune, "unity of mind and feeling"

σοὶ δὲ θεοὶ τόσα δοῖεν, ὅσα φρεσὶ σῇσι μενοινᾷς,

ἄνδρα τε καὶ οἶκον, καὶ ὁμοφροσύνην ὀπάσειαν

ἐσθλήν·

And may the gods grant you whatever you desire in your heart,

a husband and a home, and may they bestow unity of mind and feeling,

an excellent thing (Od. 6.180-181)

This is the kind of word I would consider putting inside my new wedding band (I lost the old one somewhere in my apartment last week). But I start thinking about explaining a Greek inscription to a jeweler in my remote Midwestern locale, and my head hurts :)

image credit Pin It

Friday, June 8, 2012

Why is it always Sappho?

From the NYR blog:

Waiting at the busy intersection, it suddenly occurred to me that if the old Greek poetess, Sappho, could see what I’m seeing now, she would not only understand nothing, but she would be terrified out of her wits. If, on the other hand, she could read the poems that I had just been reading, she would nod with recognition, since, like her own, many of these new poems spoke directly of the sufferings and joys of one human being. Suspicious of every variety of official truth, they brazenly proclaimed their own, while troubled and unsure of what the person whose life they were describing amounts to. This voice, which Sappho would recognize, has continued to speak to us quietly in poems since the beginning of lyric poetry.Her modern reputation (as the founder of lyric poetry) is actually a fine revenge for the way the ancient world viewed her, as a freak of nature:

"At the same time as [Alcaeus and Pittacus] flourished Sappho, a marvellous creature (thaumaston chrema): in all recorded history I know of no woman who even came close to rivalling her as a poet." (Strabo, Geography)image credit

Pin It

Monday, June 4, 2012

'My secret novel'

Madeline Miller has a delightful article up here about how she came to write The Song of Achilles despite her early distaste for classical adaptations. I hope her SO revised his opinion:

When I finished the first chapter, I made the mistake of telling my classicist boyfriend. He accused me of writing “Homeric fan fiction”.“Do you really think that you could ever be as good as Homer?” he asked.I twisted my hands, guiltily. Of course I didn’t. “But maybe the piece could still be good, just on its own?”Pin It

Saturday, June 2, 2012

Mythology and Place

I have been thinking a lot lately about place: the significance of actual, physical locations. Ancient Greece and Rome are often described as essentially imaginary places. The ability to conduct a productive career in Classics with only occasional, brief visits to modern Greece and Rome supports that idea to a certain extent.

Yet the popular imagination inevitably connects the civilization and the place. Innumerable articles make cutesy references to Zeus or Socrates before getting down to a discussion of the current economic crisis. Visitors flock to an Athenian cave because it's billed as 'Socrates' prison'.

Entirely fictional worlds can seem real too, with a wealth of invented detail often substituting for a basis in real-world history. There are no doubt many classicists who loathe the fiction of Tolkien and George R.R. Martin, but many more who find these fictive environments highly congenial, with their emphasis on myth and the moral imagination.

Ultimately we may love visiting the places where our favorite authors and historical figures lived for the same reason that we once loved tree houses and backyard forts.* They allow our imaginations, so often squelched in the pursuit of scholarly rigor, free rein.

*I'm thinking primarily of literary scholars rather than archeologists, although I'm sure they also experience an imaginative connection to their work.

Pin It

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)